CHANOYU,

as the tea ceremony is called in Japan, is a meditative ritual involving a

group of participants and a gathering of objects, the ultimate purpose of

which is to reveal the profound sacredness at the foundation of the everyday

acts of our lives: of eating, drinking, moving and interacting with people

and objects. It is a lesson in

the art of living fully and deeply, experiencing and gratefully appreciating

the everyday miracles of existence.

Most

people have their first encounter with the tea ceremony through a public

demonstration of that part of the ritual in which a bowl of tea is made.

Isolating this single aspect from the whole has had the unfortunate

result of giving the false impression that chanoyu is cold and stiff.

In fact, the full tea ritual, of chaji, is three or four hours

in length, and involves the host and his or her assistant, five guests and

several helpers in the kitchen. Before

the tea is made, charcoal for the fire to boil the water is laid in front of

the guests and a meal of seven courses is served, including generous

pourings of sakč. If the chaji

takes place during the night or early morning hours it is done by

candlelight. There is talk,

conviviality and laughter. Yet everyone involved is also aware of the responsibility of

fulfilling their prescribed roles in a way that smoothly and unobtrusively

contributes to the success of the event and the good of the whole.

Through the experience each participant’s body, mind, heart and

spirit are being nourished.

The

guiding principles of chanoyu are Wa, Kei, Sei, Kaku (Harmony,

Respect, Purity and Tranquility). It is believed that if the first three are

present, then tranquility will follow naturally.

An expression, which is also often used, is Ichigo Ichie (One

time, one meeting). It serves as a reminder not only during the tea ceremony

but in our daily lives to stay awake and aware of each moment in time, which

is unique, precious and unrepeatable. In Japan, an entire culture has

evolved to support and enhance this ritual. Tea has become the embodiment of

the arts of traditional architecture, gardens, ceramics, lacquer, baskets,

metalwork, kaiseki cooking and Zen painting and calligraphy.

It

is the duty and pleasure of the host in planning the event to give great

thought to providing the best and most inspiring experience for the guests.

The objects the host elects to use will together weave a story and evoke a

feeling that will slowly be revealed during the course of the chaji. There

will always be a seasonal reference. The story is told in part through the

seasonal appropriateness of the food and objects themselves, but mainly

through the words of the scroll and the poetic names, which have been given

to some of the utensils. These names and the history of the objects are

discussed as a vital component of the ritual. The objects are customarily

named not by the host, but by a Zen teacher or tea-master who has carefully

and intuitively studied the object and given it a poetic name that emphasizes

the subtle qualities the object evokes.

These names are written on the wooden boxes in which the objects are

stored.

The

utensils are also chosen with a strong regard for the way they harmonize and

interact with each other. This

harmony does not mean blandness of any sort, however, and often includes

somewhat startling and unexpected contrasts designed to underscore and

enhance the unique beauty of each object.

For example, among ceramics of an elemental and rustic taste will be,

perhaps, a gilded porcelain utensil of refined decoration.

Of

all the objects that will be brought together in the performance of a tea

ceremony, the scroll that is the writing of a Zen priest is unequivocally

the most important. It is the

first thing seen upon entering the tearoom and the only object that is honored

with a bow. The words

of the scroll will set the theme of the tea, but more importantly, it is

thought that through the medium of the ink on paper and the intentionality of the priest at the time it was brushed, the character and spiritual power

of the writer is present in some way as the guiding influence of the tea

event. In Japanese, the

writings of Zen priests are called bokuseki, or "ink traces" in English.

The bow is meant to show respect for the writer of the scroll and the

spiritual meaning of the words.

Ceremonial

tea drinking and Zen practice have been intertwined since they were brought

together to Japan from China at the end of the twelfth century.

But chanoyu did not come into its full flower until the sixteenth

century, under its great patriarch Senno Rikyu (1522- 1591).

He was a man of aesthetic genius and the arbiter of taste in his

time. His creativity and

discrimination form the foundation of tea as it is practiced today, as well

as what is thought of as uniquely Japanese taste.

Among his accomplishments are the development of raku pottery and

kaiseki cuisine.

Rikyu

was born into the merchant class, became a tea-master who served in this

capacity under the military ruler of Japan, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) and

achieved fame as tea-master to his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598).

He studied with two important tea-masters of his day, Kitamura Dojin

(1504-1562) and Takeno Joo (1502-1555) and was greatly influenced in the

development of his taste by the earlier figure, Murata Shuko (died 1502).

Zen calligraphy was first used in the tea ceremony by Shuko.

His Zen teacher, the legendary Ikkyu Sojun (1394-1481) presented

him with a treasured scroll of the calligraphy of the Chinese priest Engo

Kokugon (1063-1135) as an acknowledgement of Shuko's enlightenment.

This began the custom of hanging the writing of a Zen priest at the

tea ceremony.

Rikyu

pursued his own study of Zen at Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto with Kokei Sochin

(1532-1597), with whom he had a long and close friendship.

Although Rikyu owned many ancient treasures, including the Engo

calligraphy which he often used in his tea gatherings, he also began the

until then unprecedented custom of using the calligraphy of a living Zen

priest by hanging the writing of his friend and teacher Kokei.

In

addition to the main scroll in the tearoom, which is most often calligraphy,

another scroll will be presented in the waiting area where the guests gather

prior to entering the tearoom together.

This scroll will be of a less serious nature, and will often be a

painting.

It

will always have some relationship to the primary scroll, and help in

developing the theme. In tea

taste, repetition of anything is strongly avoided but things are chosen for

their subtle cross-references.

Because

of the importance of acknowledging the changing seasons in chanoyu, the

first eight scrolls were chosen to illustrate what would be appropriate

paired scrolls for tea ceremonies held in spring, summer, fall and winter.

All of the scrolls shown in this article were brushed by Japanese Zen

priests. The translations are

by John Stevens, with the exception of the seventh scroll, which is by

Stephen Addiss.

|

|

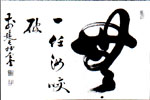

The

first scroll* by Rozan Eko (1865-1944) is appropriate for spring in the

waiting area as the gourd shape is a reminder of the hollow dried gourds

used as traditional sake containers which were taken on cherry blossom

viewing picnics as part of the celebration of the coming of spring.

The words say: A fragrant wind, flowers, and the moon |

|

Although

the shape of the gourd is abstract enough to almost be considered

calligraphic, the writing is still enclosed in a painting.

The principal scroll* to be used on this occasion, by Banryu

(1848-1935), says: Once again Heaven and Earth While both scrolls refer to spring they do so in different ways. Also, the artist of the first scroll is younger than the writer of the principal one.

|

|

|

|

In

summer it is important to evoke a cool feeling as a counter to the heat in

consideration of the guests. In

the waiting room scroll* by Deiryu (1895-1954) we already begin to have this

feeling just looking at the painting of the bamboo which seems to be

slightly in motion given the angle of the leaves and stems.

This is developed further with the words inscribed: A pure breeze rustles the leaves |

|

The

following scroll* by Kaimon Zentaku (1743- Flowing

waters by Cold Mountain Road |

|

Both

scrolls evoke a feeling of coolness through movement, but through different

elements of air and water. This

scroll also contains a subtle reference to the coming fall with the words

"Cold Mountain Road". The

best time for moon viewing is the fall, and the Chinese poet Kanzan, who

lived on "Cold Mountain", is associated with the moon, as we will

see in the following two selections for fall.

|

|

The waiting-room scroll* chosen for this fall moon viewing tea ceremony to be held at night is a painting of the two Zen figures of Kanzan and his friend Jittoku. They lived in China in the ninth century. Kanzan was a hermit poet whose poetry is highly regarded by Zen practitioners. Jittoku was the kitchen helper in a nearby monastery. He is often shown as here, holding a broom. Kanzan, the poet, is holding a scroll on which nothing is written, and the two are shown laughing as usual. |

Chingyu Zuiko (17431822) inscribes this painting:

Masters Kanzan

and

Jittoku

Always in perfect accord

Sporting together in high spirits

|

|

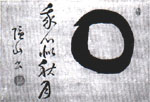

Inside

the tearoom is this Enso (Zen circle)* by Inzan len (1754-1817).

In recognition of the fall moon viewing this is an exception to the

usual practice of hanging only a scroll of calligraphy in the tearoom

itself. The words are part of

the most famous poem of Kanzan: My heart is like the Autumn Moon |

|

Winter

is part of the natural cycle which includes a time of dormancy, rest and

renewal. Sometimes this may

seem to be a period of trial and difficulty, as though nothing we do can

effect change. The harbinger of

this time is evoked by this painting* by Reigen Eto (1721-1785): Crows pass |

|

|

|

The

calligraphy* by Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768) chosen for this season reminds us

that in times that may seem difficult and as though they may never end, we

should know that we arc not alone. We

can call on the great bodhisattva of compassion, Kannon. ALWAYS IN MIND Through

this cycle of tile seasons, so important in tea, we are reminded of the

paradox of constant change within continuity.

The seasons are constantly changing, yet they are always returning. |

In

addition to the very basic and profound use of the seasons as a solid place

that tea returns to again and again, there are other cultural events that

call for chanoyu. The New Year

celebration is very important in the world of tea.

When Japan was still using the Chinese calendar new years came in

February, which seems a very appropriate ending to winter.

The following two scrolls could be used for this occasion.

New Year is a time of congratulation and good wishes.

|

This

painting of a shrimp* by Shunso joshu (1750-1839) was probably painted in honor

of the New Year, and might be hung in the waiting area. An Ocean of Good

Fortune Because

of the bent back of the shrimp it is considered a symbol of old age and long

life. So in addition to the

words, the painting itself represents good wishes. The

Oriental Zodiac has twelve animals: the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon,

snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog and boar.

Each year is presided over by one of these animals, which changes at

the New Year. |

|

|

|

The

next scroll* is calligraphy that reads "ox" in the abstract shape

of an ox. This scroll might be

a little too playful for use in the tearoom itself on any other occasion

than a New Year that begins the year of the ox. |

|

|

The

last four scrolls could be used on numerous occasions and in any season, the

first two* being appropriate for the waiting area.

The exceptionally large painting of Hotei by Mamiya Eishu (1871-1945)

reads: Hotei begs in the vast Universe The

calligraphy on the painting of Daruma, the founder of Zen in China, by

Kakugan (1793-1857) says: Spring rain opens the flowers |

|

|

|

The

last two calligraphic scrolls could be used in the tearoom itself during any

season. The scroll* by Setsudo

Genko (?- 1852) has a particularly direct Zen theme: EMPTINESS |

|

This

last gentle calligraphy* done in his old age by the great Zen master Hakuin

Ekaku (1685-1768) that follows is particularly interesting as the saying is

one of the Jodo sect of Buddhism, and not of the Zen sect. It illustrates his character very well, in that although he

was known to be very strict in Zen studies with his disciples, he would

often brush the sayings of other sects for their believers. Taking refuge in Amida Buddha |

|

|

|

Hakuin Ekaku |

||

Chanoyu has been used in the service of many causes throughout its history. Shoguns have used it to solidify their power and reward vassals; hosts have used it to impress others with their wealth, taste and sophistication; and young ladies of marriageable age have been taught proper deportment through it. However, no matter what is happening on the surface of a tea event, deep philosophical truths are being expressed through the scrolls and the physical movements of the ritual. Perhaps this was best said by Rikyu himself. Chanoyu of the small tearoom is first of all a Buddhist spiritual practice for attaining the way.